Can a collection of Persian antiquities held at a Chicago museum be used to pay damages to the American victims of a terrorist bombing in Jerusalem? That was the question argued at the US Supreme Court on 4 December, in a claim brought by Jenny Rubin and others against Iran. But the justices who questioned the lawyers involved in the case seemed skeptical about allowing the artefacts to be seized.

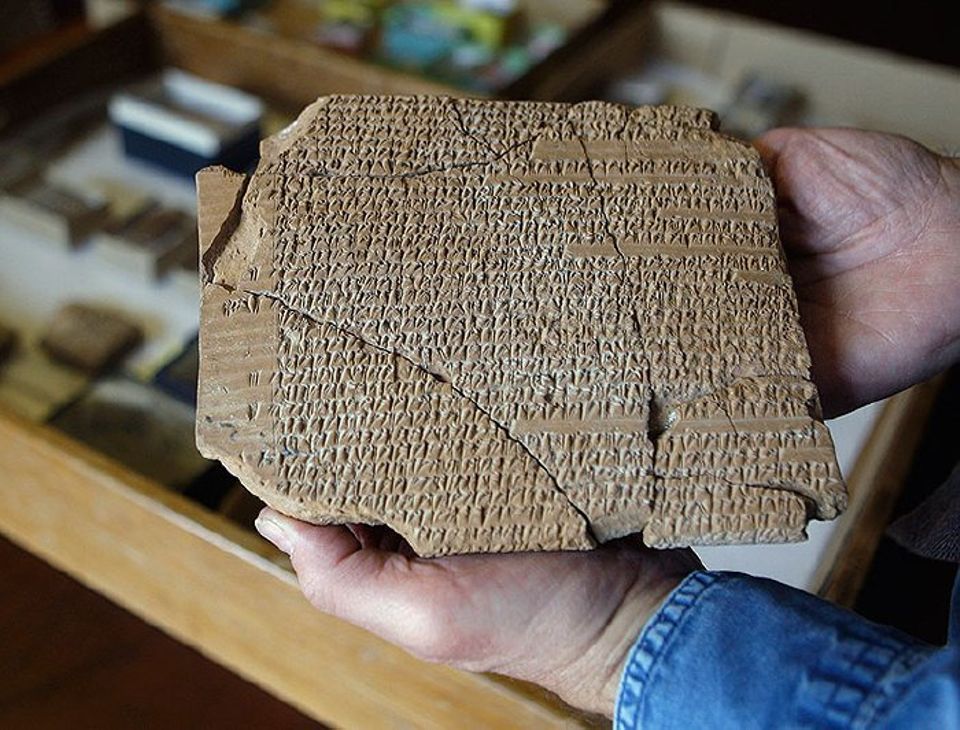

Rubin and the other plaintiffs, who were the victims of a 1997 suicide bombing in a pedestrian mall, won a $71m judgment in US court against Iran in 2003. To get paid, they are claiming the 30,000 ancient Persian clay tablets and artefacts in the Persepolis Collection at the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute, which have been on loan from Iran since 1937.

Generally, under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, a foreign nation is immune from lawsuit in the US, but there is an exception that allows victims of terrorism to sue any country that sponsored the attack. In such cases, the country’s assets have been subject to seizure if they have been used in a “commercial activity”. The Persepolis artefacts, housed in a museum and used mostly for scholarly research, are not commercial assets. But the Rubin victims say that a 2008 amendment to the immunities law means the commercial rule does not apply to terrorism victims.

The case turns on a close reading of the law. Five justices questioned the victims’ lawyer, Asher Perlin, on his textual analysis that gets rid of the “commercial activity” test. He remained undaunted, arguing that Congress had already decided that “enough is enough” and wanted to see judgments enforced against sponsors of terrorism. In 2016, Congress overruled President Obama’s veto to pass the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act, another amendment that allows the families of 9/11 victims to sue Saudi Arabia.

Justice Stephen Breyer gave the example of the sixth century BC Cyrus Cylinder. “Iran has sent it around the world. If Iran sends it to the US, can you seize it?” Breyer asked. (In fact, the Cyrus Cylinder is owned by the British Museum.) “Yes,” Perlin replied. But the lawyer added that “there is not going to be a mad rush to get antiquities” based on this case, citing a US programme that protects international cultural property on loan. The Persepolis objects came to Chicago too early to be protected by it, however.

David Strauss, the lawyer for the University of Chicago, said that the 2008 amendment only makes it easier for terrorist victims to seize the assets of a subsidiary of a foreign state when that country owes money on a judgment.

The US government is arguing against seizing the antiquities. Zachary Tripp, the assistant to the solicitor general, told the court: “The US has concerns about the reciprocal treatment of our assets abroad” if the claim on Iran’s antiquities were to succeed. “If Congress took action exposing the cultural, historical assets of a foreign nation to seizure, it would do so clearly,” he added.

When the arguments ended, the justices rose and glided out between crimson drapes, with Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the oldest member, disappearing last.