Bottles of vodka zipped around the tiny, jam-packed room in downtown Moscow, passing from hand to hand like buckets of water in a slapstick fire drill. What began as a modest birthday fete on the third floor of the Marriott Grand Hotel had become the unofficial after-party for the first Triennial of Russian Contemporary Art, and two dozen artists from nearly as many cities were celebrating. They crowded every inch of furniture and jumped on the bed. The music was soft; the rapid-fire conversation was not. If there were noise complaints, no one heard. Smokers gamely tried to exhale out the window, but a brisk wind blew back, perfuming the air with subtle notes of nicotine that wafted above boxes of half-devoured bread.

BUZZZZ! Suddenly, the grinding whine of what sounded like hardcore dental surgery interrupted. Everyone swiveled around. A local street artist had pulled out a motorized drill and started engraving an empty tumbler. He passed it on and soon the glass was completely tattooed in doodles and runes. Clothing then gave way to bathrobes and it was off to the jacuzzi, where the effervescent bunch floated until 4 a.m.

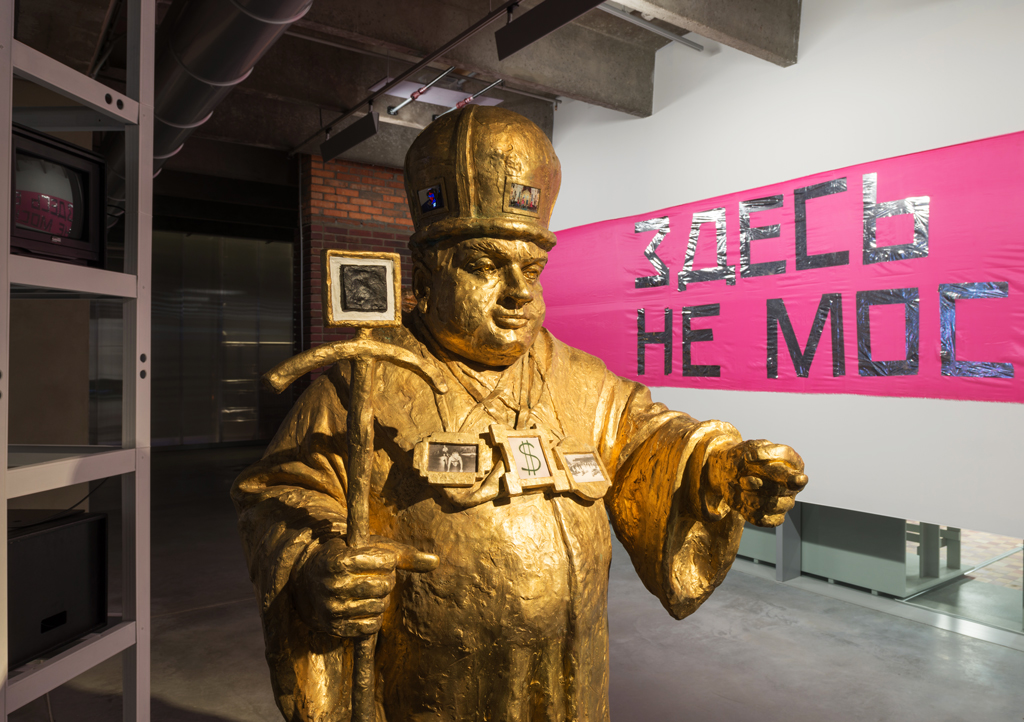

The high spirits and inclusive, madcap energy suited the exhibition: a vast, unprecedented survey of 68 Russian artists that opened a little more than a week ago and continues through May 14 at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art. Videos, photographs, acrylic paintings, animations, watercolors, wood sculptures, fabric sculptures, installations, and sundry other eclectic works filled the concrete space, a former Soviet restaurant the size of an airplane hangar in Gorky Park.

The triennial marks a turning point for Garage. Ever since moving into its current cavernous building in 2015, a glitzy crew of famous foreigners have dominated the programming. “Yayoi Kusama—yeah, that is great, but come on, what about Russian artists?” said one Moscow-born painter at the triennial’s opening. When Garage does exhibit Russians, he said, they tend to be “an older generation.”

This show acquits Garage on both counts. Over a third of the triennial artists are under 35, and they represent a wide swath of Russia, from Anadyr to Zelenograd.

“Russian solidarity is a very important goal for the whole triennial,” said Andrey Misiano, one of six curators who organized the sweeping exhibition. He and his colleagues traveled through 11 time zones (yes, Russia is that big) to discover new artists in remote, underrepresented regions.

Even contemporary art from the capital, however, is a blind spot for many foreigners. Especially in the United States, where recent reports of cyber attacks, election fraud, and political collusion abound, Russia exists in the minds of many as an opaque and fundamentally alien adversary.

For viewers who come to Garage picturing Russian art like they picture Russia—grim, gray, humorless—the triennial will offer a refreshing corrective. The museum is humming with lighthearted, irreverent work—including kinetic sculptures that bob and whir by Mikhail Smaglyuk—and ironic installations. The collective known as ZIP group, for instance, presents visitors with a landscape painting festooned with a forest of noxiously fragrant pine trees that viewers can further “enhance” with cans of air freshener.

There are also sophisticated and poignant considerations of the country’s fraught history. Aslan Gaisumov presents a stark grid of metal numbers that once belonged to homes in Grozny, the capital of Chechnya, where the artist was born the year when separatists declared independence from Russia. The city was destroyed during the ensuing conflict; these bullet-scarred plaques are all that remain. The sequence of numbers—and the voids within it—conjure human trauma and loss in terms neither didactic nor sentimental.

Garage director Anton Belov and chief curator Kate Fowle conceived of the triennial in 2015 during a visit to Vladivostok, a city so far to the southeast it’s practically in China (which, in fact, used to own it). Rallying six curators around the idea took some work, according to Belov.

“It was difficult to bring this idea on the table,” he said during an afternoon interview in the Garage café, a cozy low-ceilinged nook within the museum. “And then it was very hard that curators should go to the regions, because usually curators think they already know everything. It was hard to push them.”

But the pair’s persistence—and the curators’ extensive research—ultimately paid off. Overall, the show is a boon to local audiences unacquainted with fine art from the farthest reaches of the country, to foreign visitors, and to the artists themselves, particularly those who work in relative isolation.

The museum staff is clearly proud of fostering these kinds of connections—sometimes to the point of hyperbole. This year is the centennial anniversary of the Russian Revolution, an event that occasioned “the formation of Russian’s first avant-garde,” as the triennial’s promotional literature notes. “Garage is looking to spur the next.”

Some doubt whether, under the current political regime, Russian artists can enjoy full creative freedom. “Art is dead in Russia,” said an older collector in a Georgian restaurant some days after the triennial opened, clutching a glass of red wine. His less well-lubricated companion shot him a cautionary look. He began buying so-called “unofficial” art in the 1980s, when restrictions on abstract painting had loosened, and he still remembers the harsher years before the Thaw. “The situation now is the same as in Soviet times.”

Anastasia Shavlokhova, an auburn-haired curator at Pechersky Gallery in Moscow, described a general urge to simply blend in and avoid attracting too much attention. “Everyone is afraid to be visible,” she said.

Not everyone, said Garage curator Tatiana Volkova, back at the museum. Volkova curated the “Art of Action” section of the triennial, which showcases contentious, politically charged work from unexpected sources. Russia’s most notorious radical art group, for example, is conspicuously absent from the exhibition.

“Foreigners want to see more Pussy Riot things, but our idea is to not present what’s already well-known,” said Belov.

Instead, Volkova chose to highlight fringe feminist collectives and activists who address issues including domestic violence (which was recently decriminalized in Russia) and the repression of LGBTQ rights (public displays of homosexuality are illegal), as well as sweatshop labor and abusive psychiatric institutions. They all work without the fanfare and international media attention surrounding Russian artists who get themselves arrested.

“That was one of our aims, not to follow the stereotypes but to give space, give a voice to the artists who are not represented as much for foreigners or broad audiences in Russia,” said Volkova, her gray-green eyes emphatic beneath strong brows. She was standing beside five sewing machines that the two-year-old collective Shvemy will operate in 12-hour shifts in a performance against slave labor.

This visibility is not just important for politically active artists, said Volkova, but also those who work in out-of-the-way towns without access to grants, galleries, collectors, or museums. Resources can be limited even in Moscow. Most of the fine art academies, for instance, are state-run and provide old-fashioned technical training, which cramps the development of a cutting-edge contemporary scene.

“These governmental art institutions are very conservative, and there is a big gap between traditional academic artists who can never overcome this tradition they are taught [and those] who understand that they are very closed in this old-school format,” said Volkova. Alternative educational opportunities do exist, but they are only possible with private capital, she went on to explain. “This triennial is quite an important event in these terms,” she said. Shows like this, she noted, are only possible in Russia through non-governmental funding.

Does private patronage, critics may ask, impact curatorial freedom at Garage? The museum is, after all, primarily supported by its cofounders, the oligarch Roman Abramovic and his wife Dasha Zhukova. “I don’t know anything about cases of censorship from that side,” said Volkova, firmly. “I really believe that, here, the level of freedom is much higher than, for example, the State Tretyakov Gallery or some government institution.”

“Cases of censorship are quite rare, but they create the level of fear” that causes people to silence themselves, she continued. “Self-censorship is much actually higher and more dangerous than censorship.”

Politics may not be the most controversial aspect of the sprawling triennial. At the opening, some artists grumbled that there were too many artists from Moscow, too few from Saint Petersburg, and that the representatives from each of these cities are the obvious choices. (“Russians love to complain,” said Shavlokhova after listing some common gripes.)

The dense proximity of so many divergent works results in what some viewers termed “incoherence.” Others, somewhat less delicately, called it “chaos.”

“As a gesture, it’s great; as a show, it has serious problems,” said one Garage curator at the private opening, waving at the dizzying array behind him.

These problems aside, it was extraordinary to see so much Russian art in one place—and so many Russian artists in conversation. During the vernissage, Anfim Khanykov, an artist from Izhesk in the Western Urals, could be found stationed beside his installation: a wall-mounted wooden hand trickling plum-based moonshine into a barrel below. (It was a popular spot—especially toward the end of the party when the bar shut down.) Khanykov, an affable wizard-type with wild white curls, said that meeting so many artists from different cities, including the Muscovites with work to either side, was a rare treat.

Or that, at least, was the rough idea. Our obliging translator was slightly distracted, half-busy collecting the drizzling hooch inside an empty bottle of Perrier.