By Karla Cavarra Britton

A little-heralded house in Westchester County, New York, holds a distinguished place in the history of modern American architecture.

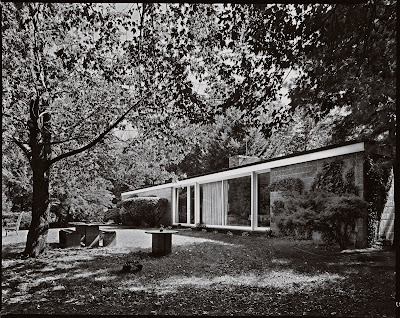

Above: A 1976 Robert Damora photo of the facade of the Booth House

Above: A 1976 Robert Damora photo of the facade of the Booth House

Photography by Robert Damora & Robert Gregson

The Booth House proved to be an archetype for the principles that would later be at work in the Glass House. The earlier house already demonstrates Johnson’s talent for creating a relationship between a structure and the natural environment. The architect’s design subtly speaks of a poetic sensitivity evident in the house’s  material precision and articulated simplicity. Elements such as the dominating island fireplace surrounded by a glazed enclosure are also already in place.

material precision and articulated simplicity. Elements such as the dominating island fireplace surrounded by a glazed enclosure are also already in place.

Unlike the Glass House, where Johnson shaped the landscape with carefully created vistas, the Booth House was set within an existing topography. Sited on the graded crest of a wooded slope, it takes full advantage of the towering trees that enclose the house. Nature enters into the house as an almost physical presence. While the Glass House has a temple-like quality, the Booth House strives to be only a comforting shelter for daily family life—a fact valued by the late architect and pioneering architectural photographer Robert Damora and his widow, architect Sirkka Damora, who acquired the house in 1955 and lived there appreciatively for 55 years.

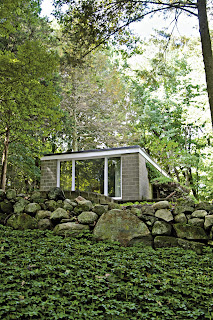

Johnson conceived a simple plan for his first commission. The intent was to provide a sophisticated modern habitation at minimal cost. The  design echoes the concept of a basic rectangular project with extensive fenestration that Johnson laid out in his article “As Simple as That,” in the July 1945 edition of Ladies’ Home Journal. Johnson’s original plan for the Booth House included a podium of gray block, which would create a level building platform on a slope that dropped ten feet across the diagonal. The house itself would sit at the rear edge of this podium, while a fourteen-square-foot studio building was to sit apart at the downhill corner of the podium. (In fact, neither the podium nor the studio was ever constructed due to budget constraints. The site was prepared by simply grading the earth. Damora eventually added a separate studio space at the top of the driveway for his photographic work, and created a windowed work space in the partial basement as an archival study.)

design echoes the concept of a basic rectangular project with extensive fenestration that Johnson laid out in his article “As Simple as That,” in the July 1945 edition of Ladies’ Home Journal. Johnson’s original plan for the Booth House included a podium of gray block, which would create a level building platform on a slope that dropped ten feet across the diagonal. The house itself would sit at the rear edge of this podium, while a fourteen-square-foot studio building was to sit apart at the downhill corner of the podium. (In fact, neither the podium nor the studio was ever constructed due to budget constraints. The site was prepared by simply grading the earth. Damora eventually added a separate studio space at the top of the driveway for his photographic work, and created a windowed work space in the partial basement as an archival study.)

Above: A view of the front entryway to the house

Saying that this first house was his own “de Mandrot house” (invoking Le Corbusier’s 1932 Maison de Mandrot in Le Pradet, France), Johnson provided for two bedrooms accessible by an open corridor, separated from the main living  area by the kitchen. The living area, in turn, is set off by the large masonry fireplace. The house is reached by an uphill gravel road, which calls attention to the subtle features of the house as one approaches it from below, heightening the awareness of the landscape as it varies with the seasons.

area by the kitchen. The living area, in turn, is set off by the large masonry fireplace. The house is reached by an uphill gravel road, which calls attention to the subtle features of the house as one approaches it from below, heightening the awareness of the landscape as it varies with the seasons.

As in the Glass House, the dominant feature of the interior is the way the solidity of the brick fireplace is countered by the immateriality of the glass walls—in this case twenty-eight feet of floor to ceiling glass that encloses most of the living space. The windows make it possible, as Sirkka Damora says, to sit mesmerized on a cold winter’s night by a warm fire in the expansive brick hearth while watching the snowflakes drift through the trees. This experience is evocative of a remark Johnson made about the Glass House: that when it snows, the house resembles a “celestial elevator.” Indeed, the Damora family recalls watching the pink light of the aurora borealis from the Booth House’s tranquil interior.

At the time of its construction, the Booth House was in the vanguard of post-war modern residential design. The house was an early experiment toward addressing the urgent need for housing following the war: in the Ladies’ Home Journal article on Johnson’s home design, architectural editor Richard Pratt editorialized on the need for research “into materials, methods, industrial co-ordination, financing and community planning—all designed to make homes better, less expensive, and more secure.”

Above: A photo of the quietly furnished living room shows the brick fireplace serves as the axis of the architecture

Prior to World War II, there had been much discussion within the architectural community regarding the need for an approach to residential design that would make quality living environments accessible to the general population. This discourse emphasized seeking economical construction, especially through new building technologies. Architects envisioned a new spatial planning for middle class people who lived without domestic help, and the intention was to de-isolate family members from each other in the course of daily tasks. A desire to integrate nature and the outdoors into a shelter also drove these design experiments.

The war put these efforts on hold, but following the peace there was an explosion of building in the United States. Many forward-thinking architects suddenly found the opportunity to realize long-dreamed of structural concepts.

The Booth House attempts to do just that. It is built of economical materials such as concrete block and plate glass. Like the early “Case Study” houses in Los Angeles, the Booth House investigated the use of unconventional construction techniques to achieve affordability. Interestingly, these explorations predate Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1947 master plan for a community in Pleasantville, New York, that introduced his Usonian concept to the Northeast.

Evocative of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House of 1951, the Booth House also speaks of a distilled architectural purity that addresses a simplified and disciplined understanding of dwelling. As Sirkka Damora puts it, “The Mies hallmark of reductive rectilinear design—with minimal interruption of the flow of space within a building and out to the exterior landscape—was clearly evident in Johnson’s architecture of the period.”

Evocative of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House of 1951, the Booth House also speaks of a distilled architectural purity that addresses a simplified and disciplined understanding of dwelling. As Sirkka Damora puts it, “The Mies hallmark of reductive rectilinear design—with minimal interruption of the flow of space within a building and out to the exterior landscape—was clearly evident in Johnson’s architecture of the period.”

Left: The north end of the house demonstrates how Johnson’s design lends grace to humble cement block

The Booth House proved to be a striking harbinger of the outpouring of mid-century modernist houses created by the Bauhaus-inspired “Harvard Five” (Marcel Breuer, Eliot Noyes, Landis Gores, John Johansen, and Philip Johnson), and other collaborators such as Victor Christ-Janer, in and around New Canaan, Connecticut, to which Bedford is adjacent. Well over 100 modern houses were constructed from 1947 through the 1970s, and given its proximity to the media capital of New York, the area became a backdrop to sell anything desired or perceived to be “modern.” In 1949, for example, an organized single-day tour of seven of the original houses drew 5,000 people.

Interestingly, many of these mid-century modern masterpieces of residential architecture acquired long-term inhabitants early in their existence. For the Damoras, their home was not only a prevailing  influence on their private family life, but also a full embodiment of their professional aspirations for what Walter Gropius called “total architecture.” When one finds an environment that both soothes the soul and expresses one’s deepest convictions about life, there is little motivation to move on. As a result, many of these houses have been away from the public eye for a half-century or more as their owners happily and quietly enjoyed these self-sufficient environments.

influence on their private family life, but also a full embodiment of their professional aspirations for what Walter Gropius called “total architecture.” When one finds an environment that both soothes the soul and expresses one’s deepest convictions about life, there is little motivation to move on. As a result, many of these houses have been away from the public eye for a half-century or more as their owners happily and quietly enjoyed these self-sufficient environments.

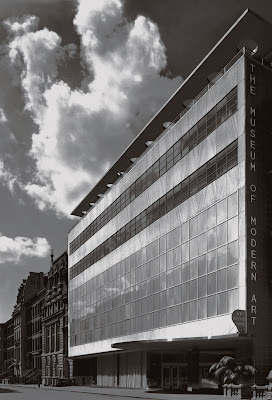

Right: In 1939, Damora took this iconic image of New York’s newly built Museum of Modern Art.

But now the original generation of owners has reached advanced years, and a number of these houses resurface to public view as they come on the market. In some regrettable cases, the houses have been bought and then demolished to make way for the larger houses characteristic of a more profligate era. Yet the Booth House still stands as a jewel from a remarkable period in modern American architecture when design, efficiency, economy, and serenity were understood to be mutually compatible and desirable. M