A legendary red swimsuit poster that sold in the millions and her role as a fetching detective on Charlie’s Angels established Farrah Fawcett as a sex symbol of the 1970s—long-limbed, feather-haired, often beaming with a thousand-watt smile. Despite a lengthy and interesting career—particularly her tough, enigmatic turns as different women reacting to the madness of men in the movies Extremities and The Apostle—Fawcett lived under a sort of pin-up shroud until her death from cancer in 2009. It is, therefore, something of a revelation to learn that Fawcett was a passionate lifelong artist and art collector. In “Mentoring a Muse: Charles Umlauf & Farrah Fawcett” at the Umlauf Sculpture Garden & Museum in Austin, Texas, some of Fawcett’s sculptures and works on paper are interspersed with art by one of her early teachers—in a surprisingly beguiling and moving exhibition steeped in a mix of melancholy and resilience.

The sturdily successful artist Charles Umlauf spent 40 years as a life drawing and sculpture professor at the University of Texas in Austin. Fawcett began her studies there as a microbiology major in 1965. College life for the Corpus Christi-born beauty had a surreal tinge to it. According to a group of life-long friends assembled at the museum for a discussion event earlier this month, when Fawcett pledged her sorority, the line of men waiting to catch a glimpse of her latticed around buildings. She had a date for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Boys carried her books to class. She was “famous before she was famous.”

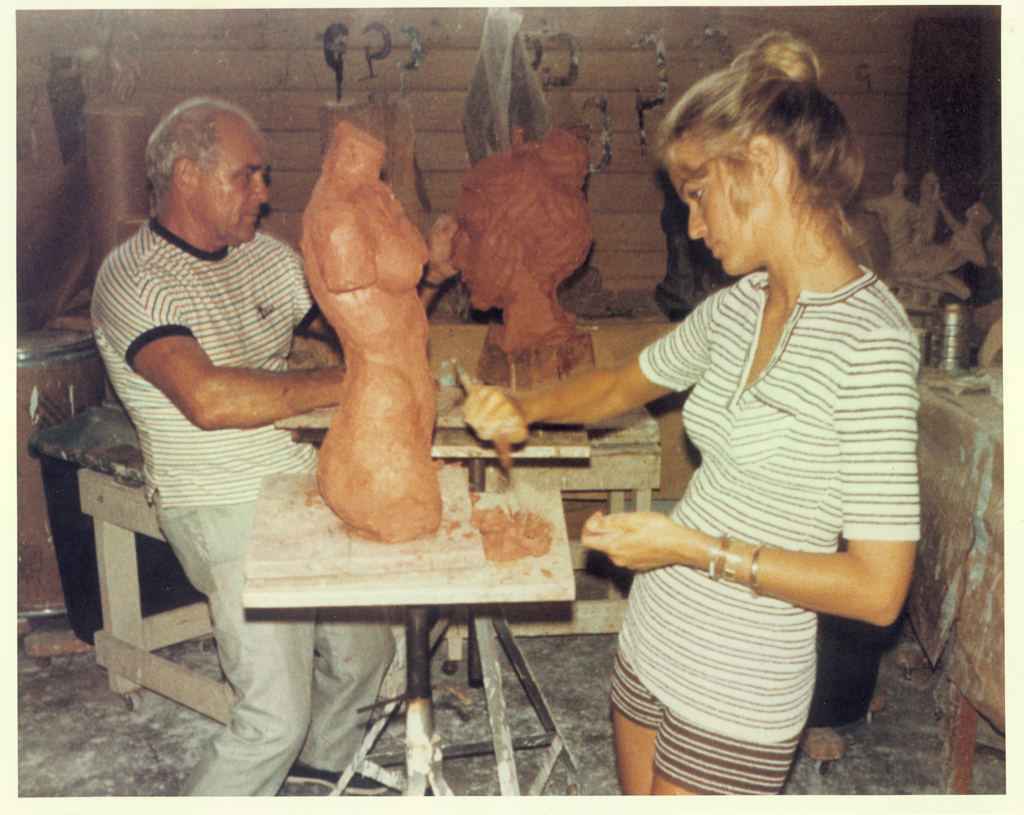

When Fawcett switched majors from science to art, Umlauf took a special interest in her, and she proved a serious student of her teacher’s rigorous, classical style. In 1968, Fawcett was convinced by persistent phone calls from agents to move to Los Angeles—she was voted one of the ten most beautiful coeds on campus for all three years she was in college, on lists that apparently made their way to Hollywood—but she and Umlauf remained close until his death in 1994. Fawcett amassed an impressive collection of Umlauf works, and he cast multiple plaster and bronze sculptures of Fawcett and her only son, Redmond. Umlauf also arranged for Fawcett’s own plaster works to be bronzed at the foundry in Italy that he himself used. What the current show illustrates is a genuine friendship characterized by an almost cinematic symbiosis: she loved him as a mentor, and he loved her as a muse. Fawcett could well have starred in a movie about the union.

When Fawcett died, at the age of 62, she bequeathed a large portion of her art collection to the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas. Katie Robinson Edwards, curator of the Umlauf Sculpture Garden & Museum, worked for several years with associates at the Blanton as well as Fawcett’s nephew Greg Walls (who inherited several works from Fawcett’s estate) to create an interlocking narrative of the works of Fawcett and Umlauf and the refuge they represented—for Fawcett, at least—from a life often marked by sadness.

one of the earliest pieces in the show, a pencil drawing titled Portrait of a Young Man (1967), Fawcett demonstrates a somber grace, depicting a haunted Texan boy—like one out of Hud or The Last Picture Show—and signing her name elegantly on one of the boy’s shirt buttons. The boy in the picture is Fawcett’s other nephew (Greg Walls’s brother), who died tragically on an oil rig. In other works, like an elegiac sculpture Fawcett made of her older sister Diane (who died nine years before her, at the same age and also from cancer), there is an astute and unsentimental understanding of mortality. The specter of death hangs over the show.

Another early work on paper is a mirthfully grotesque and scathing portrait of Fawcett’s first husband, the leathery and somewhat bloated Lee Majors. According to Ryan O’Neal’s memoir Both of Us: My Life with Farrah, Majors, the star of The Six Million Dollar Man and tennis partner of O’Neal, foolishly asked his court mate to take Fawcett out to dinner while he was filming a political thriller in Canada. After just two dates, the Fawcett-Majors union was effectively over, in favor of a new one with O’Neal that would remain for most of the rest of Fawcett’s life. Interestingly, there are no direct portraits of O’Neal in the exhibition, but there is a large photo of him with Fawcett and Umlauf all together in 1985, when Umlauf received the Art League Houston award for Texas Artist of the Year. Umlauf and Fawcett look happy; O’Neal looks sour.

Among works in the show from Fawcett’s collection is a ’80s-era napkin sketch by Andy Warhol titled F.F. Eye (for “Farrah Fawcett’s eye”) that recalls the deftness of Warhol’s early hand as a fashion illustrator. It appears in a charming corner of the show that highlights Fawcett’s affinity for Surrealism—she had works by Man Ray and Magritte in her collection—and Pop art, as well as the affection that some artists of her era—including Warhol and Keith Haring—had for her. Fawcett genially engaged in a bit of quasi-Surrealism in her own undated painting Two Faces, a competent freestyle profile of a male and female face from a skewed perspective that suggests two faces sharing one set of eyes. Competency is one of the striking features of Fawcett’s art. Nothing in the show is cringe-inducing or embarrassing, as might be expected from celebrity painting and sculpture. Even the early pieces suggest sensitive, sympathetic vision. She seems to have intimately appreciated the yearning and folly of the heart. All of the pieces have a sadness, dignity, and a sort of humor to them.

Given the influence Umlauf had on Fawcett, there are echoes and mirrors of him in her work throughout the show. But where, as the curator Robinson Edwards told me during a walkthrough, Umlauf’s sculpture of a female torso highlights the relentless masculinity (and by extension misogyny) of Umlauf’s vision and technique, Fawcett’s torso sculptures have a gentler, savvier vibe. Resistant in the ’70s to posing nude, Fawcett eventually appeared in Playboy at age 50 in 1997 (in an issue that sold 4 million copies), and one of the paper works is a self-portrait of her centerfold spread, clipped in the manner of the torso sculpture. Both in her life and in her work, Fawcett had a bemused and canny understanding of sex and the power and currency of the female body. In 2009, considering the success of Charlie’s Angels, she told a reporter from Vanity Fair: “When the show got to be number three [in the ratings], I figured it was our acting. When it got to be number one, I decided it could only be because none of us wears a bra.”

What lingers most in the exhibition, which remains on view through August 20, is a ghostly Self-Portrait (circa 1970) on a gauzy white background. Fawcett looks mournful and knowing, as if aware of how rare, regardless of fame, it is to actually be seen. The weight of glamour and desire is present in the painting, pulling Fawcett into a blank void. Like the show as a whole, it articulates part of the vindicating but also vanquishing power of fame, which can be a curse even after death. In the words of Sylvia Dorsey, a friend from Fawcett’s college days present a few weeks ago at the museum event: “It’s still difficult being Farrah, even today.”