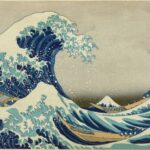

London.- “John Martin: Apocalypse” at Tate Britain will chart the rise, fall and resurrection of a unique artistic reputation. Trained as a coach-painter in the North of England, Martin went on to create some of the nineteenth-century’s most widely exhibited works of art. The exhibition will showcase the full range of his most important oil paintings, including “Belshazzar’s Feast” 1820 (on loan from a private collection and not seen in public for over 20 years) and “The Great Day of His Wrath” 1851-3, which toured the world after his death, thrilling audiences from New York to Sydney with their painstaking detail and epic sense of scale and drama. His iconic mezzotint illustrations for The Bible and Milton’s Paradise Lost will also be on display, alongside his brilliant landscape watercolours. Martin’s profound scientific interests will be shown in his pioneering illustrations of dinosaurs, based on the latest fossil discoveries, and in his unrealised but visionary engineering projects, including plans for the embankment of the Thames and a metropolitan railway for London. “John Martin: Apocalypse” will be on view from September 21st through January 15th 2012.

John Martin was born in July 1789, at Haydon Bridge, near Hexham in Northumberland, the 4th son of Fenwick Martin, a one time fencing master. He was apprenticed by his father to a coachbuilder in Newcastle upon Tyne to learn heraldic painting, but owing to a dispute over wages the indentures were canceled, and he was placed instead under Bonifacio Musso, an Italian artist, father of the enamel painter Charles Muss. With his master, Martin moved from Newcastle to London in 1806, where he married at the age of nineteen, and supported himself by giving drawing lessons, and by painting in watercolours, and on china and glass. Martin began to supplement his income by painting in oils, some landscapes, but more usually grand biblical themes inspired by the Old Testament. He was heavily influenced by his childhood experiences. His landscapes have the ruggedness of the Northumberland crags, while vast apocalyptic canvasses, like ‘The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah’ show his intimate familiarity with the forges and ironworks of the Tyne Valley as well as the words of the Old testament. His timing could not have been better. In the years of the Regency from 1812 onwards there was a fashion for such ‘sublime’ paintings, encouraged by the publications of travellers returning from the Grand Tour or the Middle East with exotic tales of places like Ur and Babylon, Pompeii and Alexandria.

Martin’s break came at the end of a season at the Royal Academy, where his first great biblical canvas ‘Sadak in Search of the Waters of Oblivion’ had been hung – and ignored. He brought it home, only to find there a visiting card from William Manning MP, a governor of the Bank of England. Manning wanted to buy it from him. Such influential patronage propelled Martin’s career onto a major stage though he was never, to his disgust, elected to the Royal Academy. This promising career was interrupted though, by the death of his father, mother, grandmother and young son – all in a single year. Another distraction was his brother, William, who frequently asked him to draw up plans for his inventions, and whom he always indulged with help and money. In 1818, on the back of the sale of the ‘Fall of Babylon’ for more than £1000, he finally rid himself of debt and bought a house in Marylebone, where he came into contact with a wide range of artists, writers, scientists and Whig nobility. His triumph was ‘Belshazzar’s Feast’, of which he boasted beforehand, “it shall make more noise than any picture ever did before… only don’t tell anyone I said so.” Five thousand people paid to see it. It was later, in a superb historical irony, nearly ruined when the carriage in which it was being transported was struck by a train at a level crossing near Oswestry in 1841, with John Martin himself on the footplate, Isambard Kingdom Brunel ran a train at 90 mph to disprove Stephenson’s theory that locomotives could not go faster than horses.

In private Martin was passionate, a devotee of chess, swordsmanship and javelin-throwing as well as being a radical who won a reputation for hissing at the National Anthem in public. Nevertheless, he was courted by royalty and presented with several gold medals, one of them from the Russian Tsar Nicholas, on whom a visit to Wallsend colliery on Tyneside had made an unforgettable impression: ‘My God,’ he had cried, ‘it is like the mouth of Hell.’ Martin became the official historical painter to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg who later became the first King of Belgium, where he constructed Europe’s first major railway. Leopold was the godfather of Martin’s son Leopold, and endowed Martin with one of Belgium’s first knighthoods, the Order of Leopold. Martin frequently had early morning visits from another Saxe-Coburg, Prince Albert, who would engage him in banter from his horse, Martin standing in the doorway still in his dressing gown, at seven o’clock in the morning. Martin, and his highly intelligent wife Susan were warm and affectionate friends to many, but he was also a passionate defender of deism, evolution (before Darwin) and rationality. Georges Cuvier, the great French naturalist, became an admirer of Martin’s, and he increasingly enjoyed the company of scientists, artists and writers – Dickens, Faraday and Turner among them. He began to experiment with mezzotint technology, and as a result was commissioned to produce 24 engravings for a new edition of Paradise Lost – perhaps the definitive illustrations of Milton’s masterpiece. Politically his sympathies were radical and among his friends were counted William Godwin, the ageing reformed revolutionist, husband of Mary Wollstonecraft and father of Mary Shelley; and John Hunt, co-founder of The Examiner. Much Victorian railway architecture was copied from his motifs, including his friend Brunel’s Clifton suspension bridge. Martin’s engineering plans for London which included a circular connecting railway, though they failed to be built in his lifetime, all came to fruition later. This would have pleased him inordinately – he admitted he would rather have been an engineer than painter. John Martin died on the Isle of Man in 1854. He is buried in Kirk Braddon cemetery.

In private Martin was passionate, a devotee of chess, swordsmanship and javelin-throwing as well as being a radical who won a reputation for hissing at the National Anthem in public. Nevertheless, he was courted by royalty and presented with several gold medals, one of them from the Russian Tsar Nicholas, on whom a visit to Wallsend colliery on Tyneside had made an unforgettable impression: ‘My God,’ he had cried, ‘it is like the mouth of Hell.’ Martin became the official historical painter to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg who later became the first King of Belgium, where he constructed Europe’s first major railway. Leopold was the godfather of Martin’s son Leopold, and endowed Martin with one of Belgium’s first knighthoods, the Order of Leopold. Martin frequently had early morning visits from another Saxe-Coburg, Prince Albert, who would engage him in banter from his horse, Martin standing in the doorway still in his dressing gown, at seven o’clock in the morning. Martin, and his highly intelligent wife Susan were warm and affectionate friends to many, but he was also a passionate defender of deism, evolution (before Darwin) and rationality. Georges Cuvier, the great French naturalist, became an admirer of Martin’s, and he increasingly enjoyed the company of scientists, artists and writers – Dickens, Faraday and Turner among them. He began to experiment with mezzotint technology, and as a result was commissioned to produce 24 engravings for a new edition of Paradise Lost – perhaps the definitive illustrations of Milton’s masterpiece. Politically his sympathies were radical and among his friends were counted William Godwin, the ageing reformed revolutionist, husband of Mary Wollstonecraft and father of Mary Shelley; and John Hunt, co-founder of The Examiner. Much Victorian railway architecture was copied from his motifs, including his friend Brunel’s Clifton suspension bridge. Martin’s engineering plans for London which included a circular connecting railway, though they failed to be built in his lifetime, all came to fruition later. This would have pleased him inordinately – he admitted he would rather have been an engineer than painter. John Martin died on the Isle of Man in 1854. He is buried in Kirk Braddon cemetery.

Tate Britain is the national gallery of British art. Located in London, it is one of the family of four Tate galleries which display selections from the Tate Collection. The other three galleries are Tate Modern, also in London, Tate Liverpool, in the north-west, and Tate St Ives, in Cornwall, in the south-west. The entire Tate Collection is available online. Tate Britain is the world centre for the understanding and enjoyment of British art and works actively to promote interest in British art internationally. The displays at Tate Britain call on the greatest collection of British art in the world to present an unrivalled picture of the development of art in Britain from the time of the Tudor monarchs in the sixteenth century, to the present day. The Collection comprises the national collection of British art from the year 1500 to the present day, and international modern art. Some of the highlights of the Tate collection of British art include rich holdings of portraiture from the age of Queen Elizabeth I; of the work of William Hogarth, sometimes called the father of English painting; of the eighteenth-century portraitists Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds; of the animal painter George Stubbs; of the artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood who revolutionised British art in the nineteenth century; and in the twentieth century of the work of Stanley Spencer, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Francis Bacon and the Young British Artists (YBAs) of the 1990s. The very latest contemporary art is presented through the Art Now programme and the annual Turner Prize exhibition. Special attention is given to three outstanding British artists from the Romantic age. William Blake and John Constable have dedicated spaces within the gallery, while the unique J. M. W. Turner Collection of about 300 paintings and many thousands of watercolours is housed in the specially built Clore Gallery. Visit the museum’s website at … http://www.tate.org.uk/britain